OHwA S01E01

March 5, 2020

Office Hours with Arbitrage #1

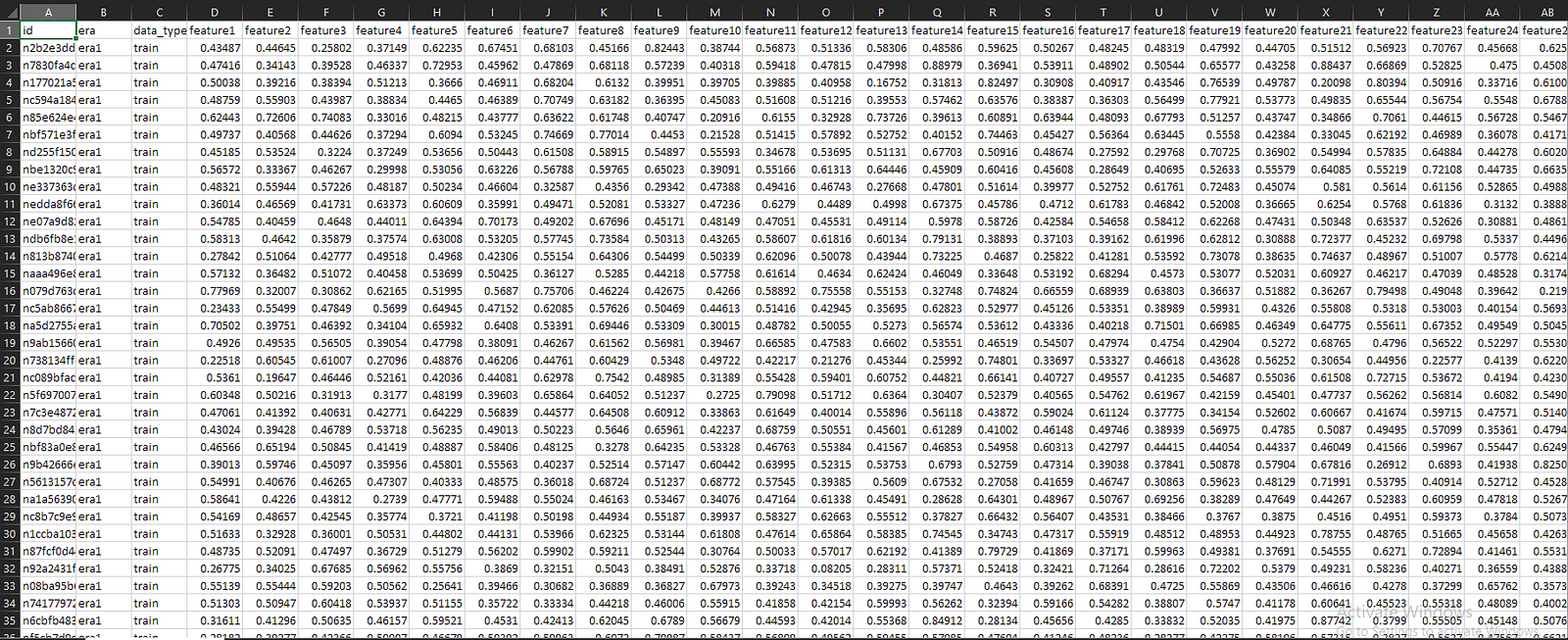

If you’ve ever entered Numerai’s data science tournament or you’re active in the RocketChat, you’re probably familiar with Arbitrage. A third-year PhD Student studying finance and focusing on Fintech and Bank Distress, Arbitrage has been involved with the Numerai tournament since 2016 (often ranking in the top 100 users), and teaches several finance courses including Financial Machine Learning with Python where he uses Numerai data.

In early March, Arbitrage held his first office hours for users to talk about the tournament at a high level and get help and feedback on their models. Here’s a recap for those who couldn’t attend or want to revisit any of the discussion.

Watch the video recap here.

Questions from Slido

Arbitrage began by answering questions from Slido, which was shared in advance of the office hours to collect questions from the community.

Can you summarize the circulation changes to Numeraire since the beginning and talk about current float?

Originally, there were to be 21 million Numeraire (NMR). The initial distribution included about two million tokens, of which not all were shipped and many were locked up, making this difficult to track over time. The biggest change came in 2019 when Numerai reduced the maximum supply to 11 million NMR, dramatically shifting the possible circulation. Learn more about the change here.

Many of the tokens from the initial distribution went to public float, and a portion being locked because they were never withdrawn (or someone lost their keys). Arbitrage also pointed out that a lot of tokens were burned, noting that because of all of this, he’s unsure of the exact amount of NMR in public circulation but noted it’s nowhere near the maximum.

Can you explain more about your suggestion for burn insurance?

“Since we’re blind to the data, we have no way to control our model’s systemic risk. So if we can’t model for it, how can we be liable for it?” Arbitrage’s point is essentially that if the ultimate goal is model stability, there should be a mechanism to help protect against volatility.

Changes in the data, he said, have reduced volatility over time and have already done a lot to address this issue, citing the differences between his previous training on the validation eras compared to his current model performance (noting that he hasn’t changed his actual model much).

What top 3 tips can you share for performing well on live data?

Don’t forget the eras. Arbitrage suggested making sure your data is structured to account for that, such as averaging across different groups of eras. “The key here is to think about it in terms of stocks,” he said. “If we presume that an era is a month, and within each month we have a set of stocks, and we have 120 training eras, then it’s possible that we have 120 observations of a single security. If that’s true, we have to treat that differently, we’re not able to use panel methods because we can’t tag the ID’s. So it would be bad to have all 120 observations in a single pool because we would overfit on the data, and that’s why we treat the eras separately.”

Don’t just use Validation as a holdout set. Arbitrage recommended using a much larger holdout set, potentially even half of the data. “When I started out, I didn’t touch the validation data. I just split the data right in half and used the first 60 eras as training data, found the parameters I thought were good, and then tested on the other half of the training data. It was grossly overfit. Then, I trained on the first two-thirds of the training data and readjusted the parameters and iterated that way, adding a bit more each time, and it wasn’t until I thought I had it that I peeked at the validation set.”

Look at the correlation scores. Over time, Arbitrage said, between 3.6% and 4.4% correlation seems to perform well on live data. He added that based on his observations, anything over 4.8% is likely to be overfit and return poor results.

Can you prove that Numerai can use high MMC (meta-model contribution) predictions in ways that add value to the hedge fund (without hand waving)?

Basically no. Because Numerai is using a bootstrap method to calculate MMC, so they’re doing repeated sampling. If all of the models were present, clusters wouldn’t matter as much as individual models along an efficient frontier; any individual model that created a portfolio that fell on the efficient frontier would probably be selected.

However, Arbitrage also noted that this would most likely lead to only five or six models contributing to the meta-model which isn’t good. “That’s why I argue that similarity isn’t a bad thing- if anything, it boosts the significance of that modeling technique.” As an example, he said if he was the only person who had a model in a cluster with a very high MMC, that doesn’t mean his model is any good (just not correlated). But, if Arbitrage exists in the cluster with, for example, other high performing models, that validates his methodology works.

“I think it’s important that we have 30- 50- 150- 200 people all using the same methodology but slightly different because the benefit is that we’re independently validating the methodology and staking on it separately… without that we just have a hodgepodge of users doing well randomly.”

As a final point, Arbitrage added that the current configuration of MMC is very robust, but doesn’t give data scientists the ability to see what any given model is directly contributing to the meta-model, it’s only an estimate.

Author’s note: successfully answered without hand waving.

Can you explain what you think Numerai assets are (market, investment type, etc), by taking into account what we know over time?

Numerai has already disclosed that they trade global equities, Arbitrage said, noting that this information has been public for a while. Based on how the tournament data is structured, their evaluation period is long (otherwise the models would need to be checked every second, which would require significant computing power beyond what most individuals have access to).

Any intuition why regression seems to work better than logistic targets or multi-class classification?

Arbitrage intrepidly admitted he doesn’t know, suggesting it’s most likely a product of how Numerai sets up the data.

“I’m just glad it’s a clean data set.”

As to why the data no longer has a classification target, Arbitrage speculated that, “what they’re really looking for is for us to put a number on it; a continuous measure of what we think a stock will do,” adding that correlation seems to be working well.

Is there any promising field, theory, algorithm, or approach you think will be useful for Numerai-like problems?

Though empirical research in finance (Arbitrage’s area of focus) is vastly different from algorithm design or machine learning, he noted that dynamic asset price theory is intellectually interesting (if unrelated to the tournament).

If we’re collectively analyzing how capital can be deployed into markets in effort to ensure that anyone entering a market can get a fair price, Arbitrage explained, that makes sense. However, the “drive to find an edge” is very difficult, “and that’s why I think this is the most difficult machine learning challenge in the world — because we’re all fighting for a half to one percent edge that disappears frequently.”

Ultimately, though, Arbitrage said that within his spheres, there really isn’t anything new that would be applicable to Numerai-like problems. He explained that no new asset classes have been introduced into finance since around the 1950’s, with cryptocurrencies as a recent exception (noting as well that derivative assets might qualify, though fundamentally they still represent intrinsic value so the primitives are the same as older asset classes).

Since we know little about the assets or how predictions are utilized, why do you think there are historical limits on the hedge fund’s earning capacity?

One of the limits for hedge funds is scale:

“When you find an edge, trading on it collapses that edge because you’re making it more efficient. When you find an edge in finance, you are therefore finding something that is an inefficiency in the market and by trading on that inefficiency you are closing the profitability of it.”

This presents a problem for hedge funds in finding a strategy that scales, which is absolutely true for Numerai as well. One of the challenges for Numerai specifically, Arbitrage said, will be around having enough stability in their investment thesis to justify getting assets under management. Arbitrage believes Numerai has been relatively stable because the time frame the tournament deals with has been consistent — the data scientists have always had a one-week lag in results and a one-month time frame.

Other challenges could come from changes in securities law somewhere that impacts the data set or another hedge fund picking up on similar signals and trading against them, neither of which could be known in advance. “That’s why there’s so many training features in the data.”

A hypothetical example would be if one of Numerai’s columns represented exposure to some asset, and lots of other funds start trading against that column, its value is diminished and it won’t have any signal. If Numerai data scientists are overloaded on that column, they’re going to get bad correlation scores because it won’t be profitable (which is why it’s so important not to overfit on any column of the data).

Arbitrage also noted that Richard said Numerai plans to introduce more columns in the future, but that they won’t be necessary to train against because the current data still works.

How much does Numeraire’s volatility affect our models’ effective sharpe ratio?

“There isn’t really an easy answer to that.”

In a hypothetical example, Arbitrage explained that purchasing 100 NMR at $10 each would result in a $1,000 fiat-equivalent stake. Should the value of NMR drop by 50%, even if a model generates a 10% return, the data scientist is still operating at a loss. The risk, he said, lies in fiat-equivalency returns which is not easy to mitigate (with one possibility being the burn insurance discussed previously).

The challenge is how to reduce volatility, encourage participation, and make payouts proper incentives while also being Sybil-resistant.

If you’re passionate about finance, machine learning, or data science and you’re not competing in the most challenging data science tournament in the world, take a minute to sign up.

Don’t miss the next Office Hours with Arbitrage: follow Numerai on Twitter or join the discussion on Rocket.Chat for the next time and date.

Thank you to Arbitrage for hosting Office Hours and for collaborating on this post.

Last updated