OHwA S01E05

April 2, 2020 / Interview with Bor

For the fifth edition of Office Hours, Arbitrage welcomed longtime tournament participant Bor who was not only ready to answer questions, but came with a presentation of his own. Before Bor could present, though, he had to make it through Arbitrage’s gauntlet.

Check out the full interview and presentation on YouTube:

Arbitrage: Bor I’d like to know, how did you discover Numerai?

Bor: I don’t remember, actually. I was looking for a way to do some machine learning and find something to do while trying to learn. I knew about Kaggle before, but I have no clue how I came to Numerai. When I joined, they had this little counter going. When you submit [to the tournament], it would show you how much money you could make (until some people realized they could just scrape test data by looking at the rate that the counter was going up. It was fun… I think I made like $80 that year.”

Arbitrage: Likewise. It was low payout but it was fun because it was so new and such an exciting idea. You started participating around the same time I did. Do you remember your start date?

Bor: I can look it up — it nicely says so on the profile pages.

Arbitrage: I just want to see if you’re older than me.

Bor: June, 2016.

Arbitrage: Ah gotcha; April 26th, 2016. I’m still waiting to interview somebody who started earlier than I did. So tell me, where do you live?

Bor: Right now, Norway.

Arbitrage: Is that where you’re from originally?

Bor: No, originally the Netherlands.

Arbitrage: So what do you do for a living?

Bor: Uh, modeling pandemics….

Arbitrage: Are you serious? That’s your job? That’s what you were doing prior to four months ago?

Bor: I’ve been doing that for the last ten years or so.

Arbitrage: That’s amazing…. So what programming language do you use and why?

Bor: Clojure, it’s a [dialect of] Lisp, and it’s about ten years old now. I was programming Ruby before and I needed something faster for one of my models when I was doing my PhD. I came from C, but I had to do a lot of text processing for my PhD and I didn’t want to use the C string libraries. Ruby was really nice for that, more like Python.

Arbitrage: That’s a pretty unique choice.

Bor: At that time, both Python and Ruby were new, so I picked one that fit easier into my mind. I tried to get into Lisps a few times, and the third time it actually worked. So I switched Lisps to Clojure. I like the language. The syntax is just: open a bracket, function(arguments) close brackets. That’s the only syntax you have, basically, and I like that.

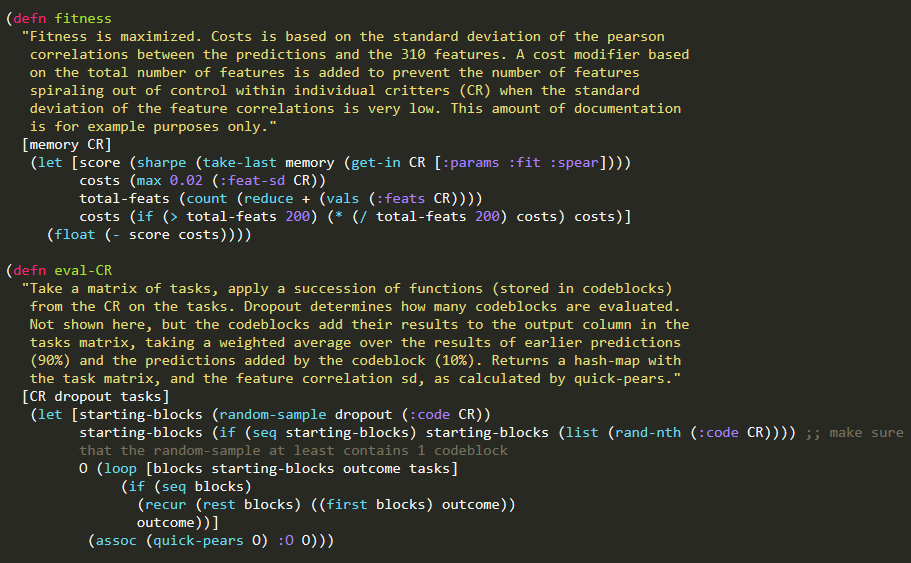

Bor was kind enough to share two snippets of his Clojure code: the first function is for fitness and the second is to help mitigate overfitting.

Arbitrage: Well that’s great because you also get to manually deal with the data while the rest of us have numerox and numerapi, and those are written in different languages. Cool — next question. Can you tell us your top three tips for the tournament?

Bor: 1. Don’t just focus on the actual technique that is doing the model fitting, spend time documenting what you’re doing so you can keep track of all of your models. 2. Spend time actually evaluating your models. Now that we can have ten accounts, keep models running longer because you can learn something from that. And the third tip would be, 3. It’s very hard to learn something from just two or three weeks of a model running and live scores. That might just be one period, so be careful there.

Arbitrage: That’s a really good point about keeping good notes. *With sadness* That’s probably something I should harp on, too, to know when you used such a model and what the parameters were at the time; if you changed it, when did you change it and when did that stake go on the board, so you can keep track of all that. I know I’ve flipped some of my models around: my third model used to be my second model, but I didn’t bother, I just changed the code in-line. Now the results are all mixed. Hard to keep it all straight. That’s a really good tip.

Bor: I used the API to unmix the results again. When I plot something for myself, I can plot [a specific] model, even if it was on three accounts over time. I can just retrieve that model, and it’s all written down in code. There is quite a lot of housekeeping that’s good to write down in code or in documentation, at least.

Arbitrage: Yeah, definitely. Who’s your favorite team member?

Bor: Slyfox, right now.

Arbitrage: There’s a vote! Somebody finally put their words out.

Arbitrage: Did you make it to ErasureCon? I don’t know if you made it out there.

Bor: No.

Arbitrage: Yeah, that’s a long trip for you. What’s your number one feature request or improvement for the tournament?

Bor: So there’s been a lot of improvements lately, to the tournament. Not having to log in and out of accounts would be nice, so the multiple accounts that are coming. I’m already happy with the change that went live just yesterday. The daily scores are moving up and down so much, everybody knows that already, and Thursdays are sort of a random lock-in moment where you get paid or punished for it and that felt weird. I’m happy that we’re now back to being basically scored on the live data and the final score.

Author’s note: read the latest on the leaderboard and how reputation is calculated in the tournament docs.

Arbitrage: And are you up to ten models now?

Bor: I’m at four. I’ve been doing, not this kind of modeling, but a different kind of modeling for a long time. What you see all these new students do is they run 50 models then look at five of them and then decide to iterate again and take up half the cluster running 50 different variants, but they only look at five of the outcomes before they realize they need to change something. I’m trying to be a bit slower in changing. Also because I’m documenting everything I do: if you do a lot of things very fast, you increase how much documentation you have to do so you have to pace a bit slower than just trying to fill up everything immediately.

Arbitrage: That’s excellent advice and I think I need to incorporate that into my PhD work. I’ve got so many regressions running right now, it’s blowing my mind. So thank you, maybe I need to slow down a little bit.

One thing I’ll tell the audience: Bor and I have been speaking for a couple of weeks now (I’ve been trying to get him on). I asked him if he could present some of his findings on the era similarities stuff we always see in RocketChat. So Bor, if you’re ready, you can share your screen and take it away.

Clustering similar eras

After Arbitrage handed over the virtual mic, Bor shared some of his analysis on the Numerai data.

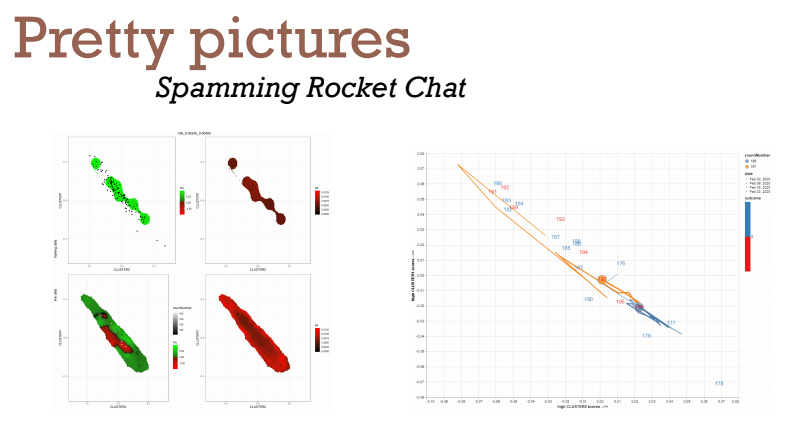

The graphs that Bor shared were part of an ongoing conversation on RocketChat around how to best cluster the eras in Numerai data in effort to identify which (if any) of the training eras are similar to the live data.

Numerai data scientists have speculated that the live data doesn’t match well with the training data. Bor wanted to investigate whether or not this was true. He said, “if you can make a subset of the training eras and say, ‘these are the relevant eras,’ that is an advantage to have.”

Tournament participants have been trying to find optimal methods for clustering the training eras. As Bor explained, this sucked their time and energy away from tuning their models and directed it towards trying to find which training eras matched which testing eras (this is no longer the case because Numerai changed the test data set In January 2020 to include previous live eras).

One way to cluster the eras is based on summary characteristics, like the average score of the features or the average score of the target in the eras. But because Numerai meticulously cleans their data, these are very small differences.

Another option is to use high-dimension cluster techniques, such as every feature == 1 dimension, and to let that reduce back to two dimensions. This technique worked better when the Numerai data had 20 features: “We were all doing the same thing back then,” Bor said, “using tSNE.” Now the data set contains 310 features.

Bor explained how he clustered eras based on model scores. “Rather than take a feature or something, I would say, ‘the performance of a single model in its ability to predict for this era is what I use as one axis. If you have a few models, you have a few axes to cluster on.”

He discovered that regardless of which method used, some eras were more alike. “If you fit your model to one era,” he said, “you will find that there will be a few other eras that you’re pretty good at predicting as well with this overfitted model. But, you’ll be very bad in other eras.”

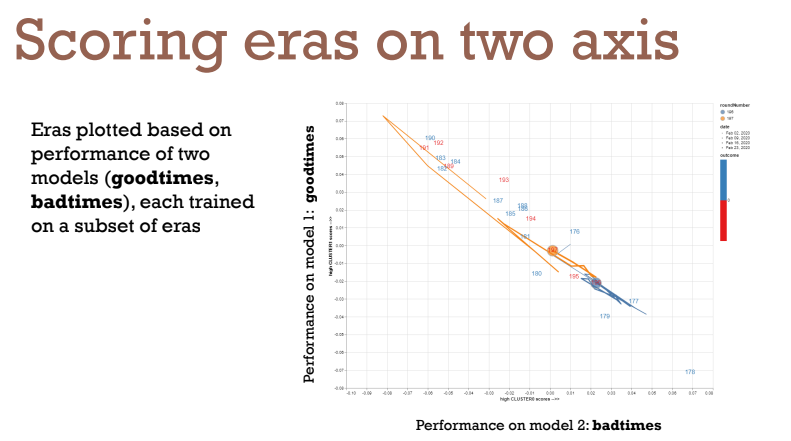

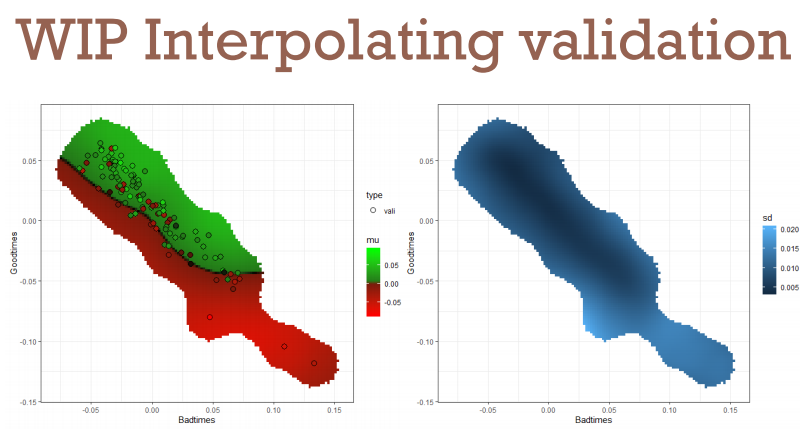

Bor plotted the performance of two models, goodtimes and badtimes:

The goodtimes model represents a period of high payouts, and the badtimes model represents a period of high burn. Bor noted that Michael Oliver pointed out on RocketChat that as long as the two models are opposites like goodtimes and badtimes (have the relationship p/1-p), then performance will always distribute along a diagonal line like the one in Bor’s plot. Bor confirmed that those two models are very close to p/1-p, despite being trained on two different subsets of 18 eras.

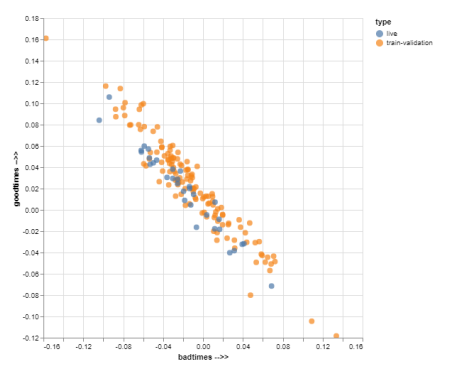

The next graph Bor showed showed the training and validation era scores for goodtimes and badtimes plotted with all of the live eras that had been released up to the point of recording (minus a few from the first few weeks of live data being available).

Michael Oliver: Are your models linear or non-linear?

Bor: Well …

Michael Oliver: Just checking

Bor: They’re genetic algorithms so both models are ensembles of hundreds of solutions.

Michael Olive: Ah okay. That’s kind of remarkable, then, for how opposite they are.

Bor: Yeah, and they’re trained independently, each on a set of 18 eras. I don’t know what’s going on. And it’s not some error in the training or validation data, because I’m guessing then the live data would have destroyed itself. I can’t really overfit to that.

Bor then explained that even though the nearly inverse nature of the two models effectively simulates plotting the era scores along one axis, the graph suggests that the live eras are still fitting quite close to the training and validation eras. He added that anyone can run this same analysis with any two long-running models.

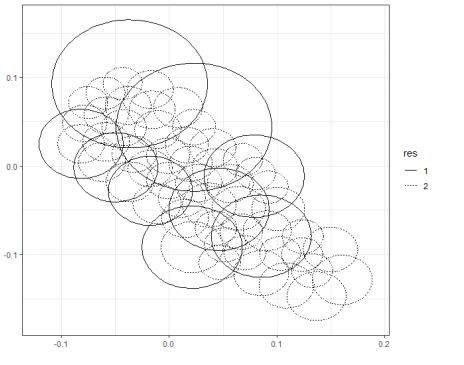

With those graphs generated, Bor moved on to interpolation analysis using fixed rank kriging to find out the average score and standard deviation of the models in a particular area.

Fixed rank kriging is a method which, given a set of data points, attempts to figure out the spatial area that is affected by the single point at the center of each circle.

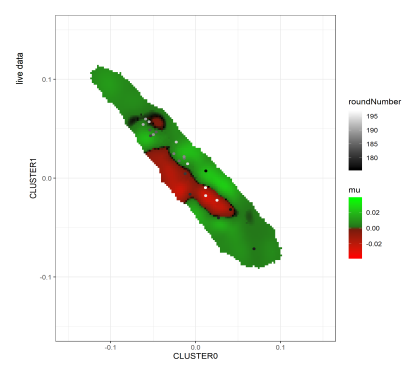

Running the same analysis on two different models, Bor generated these graphs:

One of the challenges Bor faces now is trying to determine what actions to take based on analyzing models in this way. For example, looking at the standard deviation plot and trying to determine how consistent are the high-scoring eras that correspond with the same region on the standard deviations plot.

Arbitrage: That’s amazing.

Bor: It’s fun, but I’m still trying to figure out how to do it right and how not to do it wrong. The fixed rate kriging, for example, still has quite a few parameters to fill in.

In his final slide, Bor showed an interpolation of average scores (mu) graph for one of his older models, BOR1. “It was doing quite well … but then a bunch of live eras came in to this [red] region where apparently my model wasn’t doing as well. The model was overfit, but I couldn’t see it from the validation — I could only see it when I started plotting the live data.”

With Bor’s presentation finished, Arbitrage opened the floor to questions.

Michael Oliver: I’ve tried a bunch of stuff kind of like this because ideally you want to know what cluster you’re going to be in in the live data so you can use the appropriate model. I was able to find functional clusters, but you can’t predict which one you’re going to be in (at least I couldn’t) for the live data because of the features, which is what you need to do to make this useful. Being able to say, ‘there are these clusters of functional relationships’ post-hoc doesn’t help you to predict the future unless you can get some sort of probability you’ll be in one of these clusters versus a different one. I’m curious to hear your thoughts on that and how you might go about doing that.

Bor: The main thing I want to do is have my model work along the whole range of the diagonal, basically. The eras are not equally distributed across the whole space (looking at the goodtimes model, most of the eras are one-third above midway), and if you’re training your models without being agnostic to the era distribution, the models are weighted to these periods. So I’m thinking this way: when I’m now fitting my model’s selection of eras, I try to give them eras spread across the whole diagonal so I’m not weighted. That’s the way I’m using it right now.

Author’s note: See the entirety of Bor’s presentation on the Numerai forum.

Questions from Slido

Do you know when and how Numerai actually burns our stakes, and is there a way to see this change on a weekly basis? In other words, how is it affecting circulation?

Arbitrage and Slyfox determined that this question was a perfect fit for Stephane, who readily answered.

Stephane explained that there are several components to the NMR burn process. The actual burns are only put on-chain upon withdraws but are otherwise reflected in the wallet and staking balances on a day to day basis. The burns are only put on-chain when someone withdraws funds from their agreement, which causes Numerai to close out the agreement and settle the final balance on-chain, triggering the burn on the tokens.

There is a difference between how Numerai and Erasure Bay handle burns. Because the contracts on Erasure Bay are one-time agreements, they enact immediate transactions where someone either withdraws or burns.

Arbitrage: If I increase my stake, does that trigger the meteing out as well? So if I have 100 NMR staked, I go down to 50, and then refill to 100, does that burn get enacted upon deposit?

Slyfox: It’s not just withdraws, it’s whenever you make a change to your stake, we will apply whatever changes we have in [our] database on-chain. So if you don’t make any changes at all, we’ll just continue accruing payouts and burns in the database. I’ll add one thing: why did we move to this model?

In the past, when we had weekly stakes, weekly payouts, and weekly burns. This meant we had to do one on-chain transaction for every user each week. If I pay you 10 NMR, then you burn 10 the next week, then I pay you 10 again, this actually cost us a lot of money to operate. When we burn, we burn from you, and we don’t get any of that back. When we pay, we pay out of our own pocket and we have to pay gas. The operational complexity of that was getting really high as we scale.

When we decided to move to daily payouts, we thought we could do the exact same thing except daily. Then I looked at our gas bill and it was almost more than what I was paying to all of the users [being paid to Ethereum in gas]. Stephane and I got together and came up with this new way of doing it.

Arbitrage: Thank you, Stephane.

Keno: What would I be looking for in the contract? What event logs should I be filtering for if I want to see the burn?

Stephane: We have an endpoint that allows you to track all of this — I’ll give you all more info on that.

What kind of hedge fund is Numerai? A fundamental data-driven alpha model seems like a good match, but what else? Counter spread? Quant? Long/short?

Fortunately for Arbitrage, Mr. Numerai himself Richard Craib was on the call and was willing to take a stab at answering.

Richard explained that Numerai is a global equities hedge fund driven by the machine learning models of their data science community. They’ve never traded anything besides equity, and they’re, “long/short, market neutral, country neutral, sector neutral, currency neutral, factor neutral… just trying to find the edges that other people can’t find and that aren’t exposed to the risk factors that other funds are exposed to.”

Author’s note: to hear more from Richard on Numerai, the tournament, and the hedge fund industry, check out his OH interview at Office Hours with Arbitrage #4.

Is there a difference between using R and Python? Is one better than the other? I know they should be the same, but are they? Or is one faster?

Regarding computation, R and Python should come up with the same solution, Arbitrage explained. The differences are in the language syntax and what happens on the back end.

“I use Python, I know a lot of people use R, and today we learned that people even use Ruby. I wouldn’t say that one is better than the other, they just have different uses. I teach Python to my students because I treat it as a Swiss Army knife. You can do just about anything with Python. I find that R is really good with time-series data.” — Arbitrage

Given the same set of inputs, R and Python should return the same outputs. The speed of either language is largely dependent on optimization and whether any given libraries being used are optimized for a task in that language.

How do we avoid overfitting when we use these methods [discussed by Bor] and are these algorithms useful at all?

“If they’re useful, well BOR3 is doing quite okay. I can’t tell why BOR3 is okay but it’s doing well.” — Bor

To avoid overfitting, Bor explained that he uses a maximum limit of 200 features for training genetic algorithms to avoid using all 310 and overfitting. He also limits each generation of the algorithms to seeing 10% of a given era, the fitness is determined by the last 20 eras it saw, and the era is selected at random from the group of eras Bor is training on. His fitness function is the sharpe over those 20 eras minus the feature correlation of the solution, in effort to mirror what Numerai has recommended models focus on.

Will Numerai offer a route for non-participants to stake on participants’ models for a fee paid to them and to Numerai?

“The purpose of the staking is to see if you believe in your model,” Richard said, “so if you’re staking someone else, and you’ve never seen any code and you don’t know data science, your stake is just based on some leaderboard information… It doesn’t give us very much information.”

He added that if someone is interested in NMR, they can hold NMR without being a data scientist, and if they’re not a data scientist, that’s what you can do. But regarding the tournament, Numerai wants the stakes to be meaningful and express information about the models without giving the model to them.

On top of that, Richard explained that there are legal risks in trying to have the token represent the cash flow of the hedge fund. Right now, NMR is an abstraction of user performance and there are many levels between that and the performance of the hedge fund. During those stages, Numerai performs ensembles, optimizations, trade implementations, and other transformations that aren’t part of the tournament modeling.

“I see it more like we’re buying signals: we’re buying data from our users and they’re staking on the quality of their data, rather than we’re investing in their hedge fund.” -Richard Craib

Can you talk a bit about what feature selection and/or engineering you recommend doing? What’s a good feature exposure range?

“I don’t do any feature engineering. At all,” Arbitrage said. “The data is clean, and they’ve done a really good job of smoothing out any kind of obvious relationships.”

Arbitrage said that he’s a fan of Occam’s Razor: the simple explanation is the right answer. “While Bor’s presentation was mind blowing and very fascinating, I don’t do anything close to that and I think I’m well within rank of Bor to say he and I are close in rank over time.” He pointed out that their approaches are radically different: Bor does a ton to the data, whereas Arbitrage does nothing to it.

“Which one of us is making more money for our effort? Well I’m going to claim that one because I don’t do anything to the data.”

Along with that, Arbitrage noted that feature selection is very important (and discussed at greater length in Office Hours with Arbitrage #1). “You don’t want to over sample too much,” he said, referring to Richard’s advice that the example model only looks at 10% of features at a time. Using a small sample of the feature space per iteration is very important and helps to control overfitting. “And of course treat the eras separately,” he concluded.

Feature exposure range is something Arbitrage is still figuring out. Looking at his top performing model, he noted that the feature exposure is lower than his main model, which suggests lower may be better. For his models, Arbitrage said anything above 0.08 seems too high, but he hasn’t been able to get below 0.07.

What are good strategies to reduce correlation with Example Predictions and feature exposure?

Don’t use the same model as the example model. “That’s going to give you a very different correlation. If you use XGBoost, you’re going to have a high correlation. That’s pretty much it.” He added, “If the example predictions are doing well, you want to be correlated; but to get MMC you want to have positive correlation but not too much.”

What are good approaches to ensembles in the Numerai data set?

Arbitrage suggested that any kind of ensemble will probably perform relatively well. There is a wide variety of ways to implement an ensemble, but the important thing is to still reduce feature exposure in whatever method is used.

The data is encrypted — is it really homomorphic? Are some mathematical properties lost? Our models may be tricked! Is there anything to avoid?

Richard: The homomorphic thing comes up so much, I think it’s a cool word. When we first launched … the homepage said ‘structure-preserving encryption’ in December 2015, but the blog post said ‘using encryption techniques like homomorphic encryption’ and people really latched onto us using precisely homomorphic encryption schemes. Which I did try to do, and I had the data encrypted in this way, but it turned one megabyte of data into 16 gigabytes.

Richard: The data went from normal nice numbers like you have now to very high dimensional polynomials that you had to operate on.To any normal data scientist, or even expert data scientists, it looked so weird to have these strange polynomials that you have to operate on. So I decided not to launch with that, and instead went with a different kind of obfuscation. Encryption implies that there’s a key that if you had, you could unlock it, but the data is really just obfuscated.

The other important thing to note is that there are so many phases between the raw data and the obfuscated data. The raw data, you could understand, but in the middle, just the normalization stuff that we try to do to clean the data is taking away a lot of the structure of the original data. But it makes it more normal and makes eras look more alike than they would otherwise.

If we gave away our normalized data and didn’t even do the final obfuscation, I think people would still be really confused about what it was. Maybe if you were an expert who had the exact same data, you would be able to tell something.

Has anyone mentioned creating an app for large block trades of NMR? Similar to an OTC platform?

Arbitrage mentioned that this would fall outside the scope of the tournament team and opens them up to potential risk as they can’t be involved in the market. He did add that, anecdotally, OTC trading seems to take place in London, and several organizations involved were aware of NMR.

Has Numerai ever discussed what a solution to this competition looks like? Perhaps metric thresholds i.e. MMC 2, Sortino, or Sharpe through multiple regimes?

Richard: We’ve been refining the problem while people are refining solutions to the problem,” Richard said. “We change the targets, and these new targets that are out now are an attempt at a better way of thinking about the problem. If you can be good at these targets, you’re really good. If you could be good at the previous targets, I would sometimes wonder, ‘Why do I prefer this model in position 100 over the model that’s coming in first?’ That’s really bad for the tournament. Even the users can tell that they could be at the top by making a bad model they would never stake.

What’s true right now, thinking about the feature-neutral targets or whatever future targets are going to be, we want the situation to be that a model that was in 20th but now is 25th, well we like the model that’s now in 20th even more. And that’s because we’ve refined the problem.

Ultimately, the live data is harder than the validation data so if you’ve found the solution to a great validation set, that wouldn’t be the whole answer. Things like feature exposure or other clues that we’ve noticed matter, like sharpe matters, or stationarity which we haven’t discussed much but I think is a really critical thing (where it looks like you’re playing in a casino where you have a memory-less process so your likelihood of winning next month isn’t increased if you’ve won this month). So regimes wouldn’t be a thing for your model, which is sort of what you’re talking about: you don’t see a difference between a good or bad era.

It’s kind of open ended, and that’s why no one will ever really know the answer. If we knew precisely how to frame the problem and frame the solution, we could just create a neural net ourselves. But, we need people to figure things out and stake a lot to prove that they believe in them.

Are there any rules for what Numerai can do with the NMR token or can they choose freely?

Arbitrage noted that he imagines what the team can do with the tokens is pretty heavily regulated, and Richard mentioned an earlier post from Numerai detailing their plans for the future of NMR that details some of their allocations for users and investors.

“We wouldn’t want it to be that 70% of the tokens are owned by investors who are never going to use Numerai or Erasure,” Richard said. “We think it’s very important to have that. I like the way our tokens look: there are a lot out in the community and a lot have been given away. When we sold to investors, it hasn’t been too much, and it’s often very much helped the token.”

Given a long enough time frame, do you think that Numerai can “solve” the stock market?

Arbitrage said no, because ultimately data scientists can’t model everything like regime changes (such as global pandemics). “Also,” he said, “we have rule changes like tip rules, stop limits, and all kinds of strange stuff that doesn’t even fall within the purview of the tournament that we’re not able to model ahead of time. But the very nature of what we’re doing is working to make the market more efficient. So in that sense, we’re partially solving the stock market. And the very nature of acting on signals that exist shrinks the profitability of those signals and for hedge funds, scale is one of the largest challenges they can face.”

If you’re passionate about finance, machine learning, or data science and you’re not competing in the most challenging data science tournament in the world, what are you waiting for?

Don’t miss the next Office Hours with Arbitrage : follow Numerai on Twitter or join the discussion on Rocket.Chat for the next time and date.

Thank you to Richard Craib, Slyfox, and Stephane for fielding questions during this Office Hours, to Arbitrage for hosting, and to Bor for the mind-blowing presentation.

Last updated